Street Photography and the Reflective Act

Deeper Perspectives on the Street Photographer, Ethical Challenges, and Reflection in Action

Bachelor Essay

Bachelor’s Programme in Photography | HDK-Valand | FOG237 | Autumn Term 2024

Supervisors: Julia Tedroff & Annika von Hausswolff

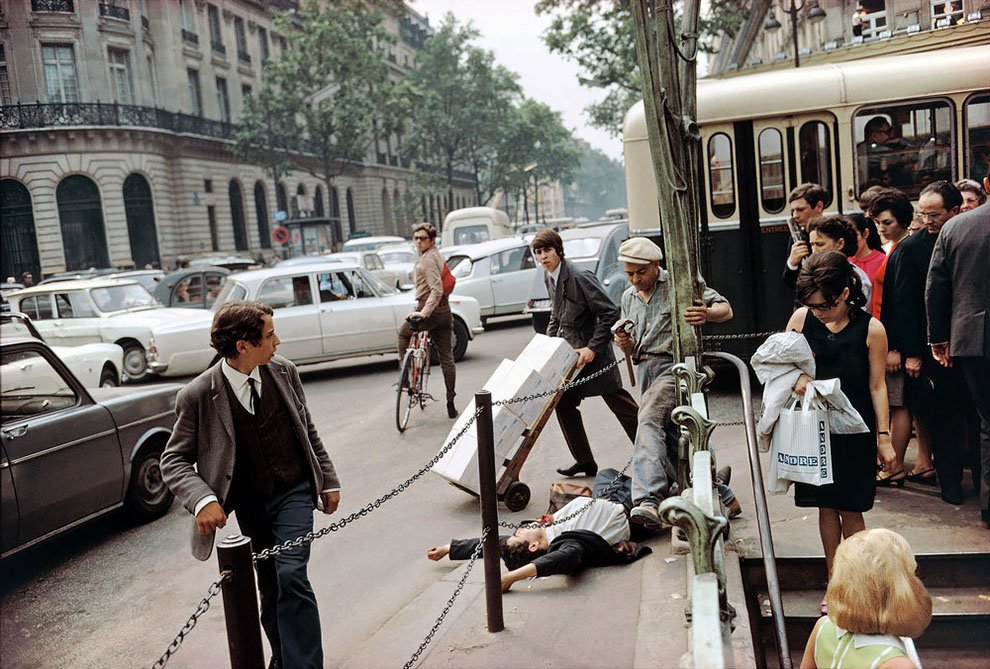

Paris Fallen Man, 1970. Joel Meyerowitz

Introduction

The phenomenon of street photography can be described as a form of visual anthropology, in which the photographer records everyday interactions and the social dynamics of streets and public spaces—often with an underlying sense of unpredictability. The genre originated in nineteenth-century Paris, where pioneers such as Eugène Atget documented the city’s environments and its inhabitants. During the twentieth century, the genre was further established through photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Helen Levitt, and Garry Winogrand, all of whom used smaller, more portable cameras to capture the fleeting moment.

In recent years, the genre has increasingly shifted from the gallery space to the digital world and social media, where it is now practiced by thousands of people worldwide. Historically, however, the genre has also been heavily criticised for violating people’s privacy, as photographers often capture subjects without their consent. Some argue that the genre exploits socially vulnerable groups for aesthetic purposes, which raises serious ethical concerns.

Street photography is relatively new to me. It is an area I had never previously been drawn to, but one that, by coincidence, became a new passion. As a personal and artistic challenge, I decided to approach strangers with my camera. What immediately struck me was the genre’s unpredictability—that anything could happen—and the sense of freedom it offered. I began to notice things I had never paid attention to before and became more curious about other people. It also became a way for me to merge with the city itself.

Gradually, I began studying the work of renowned photographers within the field and was quickly drawn to the decision-making process behind each image: how the technical, aesthetic, and ethical choices a photographer makes affect not only the appearance of the photograph, but also the people depicted and society at large. Everything leading up to the moment of exposure suddenly became almost more interesting than the image itself.

What is the aperture? What is in focus? Is the image sharp? What focal length am I using? When should I press the shutter? Am I too far away? Too close? What just happened? What is in the frame? Who is in the frame? Am I in danger? What responsibility do I have?

It quickly became clear to me that an ongoing dilemma lies in balancing artistic freedom with personal integrity. I believe these two exist in constant tension, where the photographer must navigate a very thin line to avoid overstepping or undermining either. Is there a way for the photographer to exercise artistic freedom while also navigating the ethical jungle that surrounds today’s society?

In order not to become paralysed by an endless sea of possible choices, my personal and artistic development depends on a symbiotic interplay between the physical act of photographing and the analytical reflection that follows. I needed a framework to anchor my thinking. In his book The Reflective Practitioner (1983), Donald Schön (1930–1997) introduces a theoretical model for professional development that highlights the central role of reflection in learning and the cultivation of expertise.

At the core of Schön’s theory are two fundamental forms of reflection: reflection-in-action, which refers to the reflective process occurring while an action is taking place—when the practitioner critically thinks and adapts their behaviour in real time to the unfolding situation—and reflection-on-action, which refers to reflecting afterwards on a completed act or experience to evaluate insights and draw lessons from it. In other words, the practitioner develops the ability to navigate uncertainty in real time, drawing on knowledge gained from past experience.

Although Schön’s theory cannot resolve all the ethical dilemmas that street photography faces, his model can serve as a valuable lens for identifying various approaches to the genre—where reflective ability becomes essential. Therefore, in this essay, I aim to provide deeper perspectives on the photographer, the act of photographing, and the reflection that occurs within the act itself.

Naturally, there are many photographic expressions and methods to analyse within this subject, but for the sake of structure I have chosen to categorise them into three conceptual roles: “The Observer,” “The Intruder,” and “The Camper.” The photographers I will discuss as examples of these are Vivian Maier (Observer), Bruce Gilden (Intruder), and Joel Meyerowitz (Camper).

The Observer

To begin, it seems reasonable to introduce the most common and perhaps most traditional form of street photography—The Observer. I understand this role as that of a discreet spectator who captures spontaneous moments without interfering or influencing the scene to any significant degree. This involves documenting reality from a distance, which simultaneously creates an underlying understanding of the photographer’s way of seeing the world—since we, to some extent, see through their eyes.

I therefore hold the view that The Observer possesses the ability both to see and to preserve an event intact; to leave it untouched, so to speak, without interaction or external influence. Hence, The Observer also becomes, in a sense, invisible. Photographer Greg Williams discusses precisely this and argues that the method carries a kind of innocent approach, rooted in respect for the people being photographed:

“The observer does not get in their face. The observer often deliberately hides behind the camera because he doesn't want to catch their eye and take them out of wherever they are. This could be in times of reflection, could be times of extreme sadness or extreme joy. You know something that's in some way private. Then you’re sort of stealing the moment, and that doesn't mean you're stealing it in a nasty way, but you have nothing to do with the drama that’s happening in front of you. You are simply there to record it.”

Furthermore, I believe that this “invisibility” charges the photograph with an ambivalent feeling—a kind of curiosity for the forbidden or the private. There is something both exciting and shameful about knowing that you are not supposed to look, yet doing it anyway. After all, it is not you who owns the moment; it belongs to someone else.

Someone who, in my opinion, managed to balance curiosity and respect was Vivian Maier (b. 1926), who, with a unique sense for the decisive moment, documented everyday life and people in large cities such as Chicago and New York. Her work was discovered only after her death in 2009, when collector John Maloof (b. 1981) found a large number of her negatives at an auction. The images turned out to be extraordinary depictions of twentieth-century American urban life, earning her posthumous recognition as one of the most celebrated street photographers.

Pic. 1–8 – Vivian Maier, Street 1–5 (unknown year)

Besides Maier’s visual storytelling—which greatly appeals to my own aesthetic preferences—what fascinates me most is her ability to capture human and fleeting moments from such an incredibly close distance. What stands out most prominently in her work is the fact that the people depicted are often unaware of Maier’s camera or even of her physical presence. This detail seals the entire moment within a kind of bubble, where the audience, through the photograph, gains insight into something deeply private.

I hold great respect for this ability, since I know from personal experience how difficult it is to achieve in practice. As The Observer, the photographer must be able to read situations, understand where people’s attention is directed, and know how their own behaviour might attract—or avoid—attention.

However, the moment the people depicted lose editorial control over their own representation, a problem arises. Because they are unaware of being photographed, all further handling of their image is now in someone else’s hands. The photograph may be placed in contexts or presented in ways that could exploit or harm the subject.

In his essay “Private Lives, Public Places: Street Photography Ethics” (1987), A. D. Coleman argues that street photography often entails exploitation of the people whose images are taken. He illustrates this through a personal experience involving a photograph of his son, taken during a medical emergency in which his son injured his arm. The picture eventually ended up with a photo agency that later wanted to use it in a book about child abuse. Although the injury had nothing to do with abuse, the image could have been placed in a false context—something Coleman strongly opposed.

For him, it was not merely a question of misrepresentation, but an ethical issue concerning respect for his son’s privacy. He wrote that there exists a kind of photographer’s arrogance:

“The assumption that you waive your rights to control of your own image and declare yourself to be free camera fodder by stepping out of your front door is an arrogance on the part of photographers; it has no legal basis.”

Even though art photography is not necessarily intended for journalistic or commercial use, in today’s connected and technologically driven world there are no guarantees against misuse or decontextualisation of images—whether online or in physical form. While it is indeed legal to photograph people in public spaces, the editorial handling of those photographs is far more difficult to control. Ultimately, the problem may be seen as a kind of tension—or even a struggle—between the present (the act of photographing) and the future (the image’s editorial life and distribution).

The Intruder

If The Observer intends to remain anonymous, The Intruder aims for the opposite. Instead, this figure punctures the intact bubble of the moment and interacts with the event of the image to the fullest extent. Bruce Gilden (b. 1946) is potentially the most well-known name in these circles because of his intense and confrontational style. His artistry is characterised by a close kind of photography taken with flash, where the “moment of surprise” plays a central role in the facial expressions of the depicted people.

Gilden’s method has met mixed criticism due to its unconventional nature, due to the fact that he, in an aggressive way, confronts people in public spaces without their consent. Gilden himself, however, regards his photographs more as a personal depiction of the city rather than as an exploitation of other people. Thus, the images function as a portrait of the city’s energy, stress, and anxiety seen through the people who fascinate him.

Pic. 9, Bruce Gilden, New York City, USA. (1990) | Pic. 10, Bruce Gilden, Asakusa. Japan. (1998) | Pic. 11 Bruce Gilden, New York City, USA. (Year Unkown)

What interests me about Gilden’s work is how he breaks with conventional approaches to ethics and morality. There is something refreshing in the way he disregards social boundaries and dares to approach people without hesitation. I experience the material as raw, direct, and genuine. I see them as a sudden and instinctive interaction between an active photographer and a reactive subject, where the encounter constitutes the core of the image. As much as I admire the courage, I also fear the real situation and its possible consequences.

I find Schön’s theory highly essential in this method of working, since it largely concerns using past experiences and lessons to be able to think quickly in the moment. Because the “confrontation” in this case is so central, the photographer must have formed an understanding of how people might react, as well as how one should act oneself. At the same time, the photographer must also maintain control over their technique and not forget the visual image. Therefore, The Intruder must develop an ability that combines both technical execution and social skills.

This is, of course, nothing for which there exists a concrete guide. Rather, I believe the photographer needs to expose themselves to these situations continuously over a long period of time, in order to form an understanding — or rather a feeling — for these types of interactions. Just as Schön’s theory suggests:

“Through reflection, he can surface and criticize the tacit understandings that have grown up around the repetitive experiences of a specialized practice, and can make new sense of the situations of uncertainty or uniqueness which he may allow himself to experience.”

From my own experience as The Intruder, I remember how every image and situation felt like a new source of conflict or direct danger — as if the unpredictability of the confrontation were a language I constantly had to relearn. If, against all odds, I managed to photograph a person without experiencing a minor panic attack, the picture was disastrous. It seemed impossible to combine the two.

Through continuous practice, however, I also began to recognise patterns in social signals and could, slowly but surely, manoeuvre both technique and myself according to unique situations that had by then become familiar to me. I realised, for example, how a quick compliment about a person’s clothing works well as an argument for why their picture is being taken. Or how a swift extension of the arm can effectively direct people’s gaze in a certain direction.

The most rewarding and perhaps shocking insight, however, was that: most people don’t care.

Pic 12, Man, dog, cart. New York City, USA. (1989)

Naturally, it must be mentioned that this is a type of photography that cannot escape criticism or follow-up questions. It is problematic. Period. No matter how one looks at it, the method is intrusive and can be perceived as threatening.

What my experience tells me, however, is that if someone has a problem with being photographed, they say so. Absolutely — there is a responsibility on the photographer, but there is also a responsibility on the civilian who finds themselves on the street. Joel Meyerowitz expresses it in How I Make Photographs (2020):

“My feeling about the street, and street photography, is that the street is ours. Once you enter a public space, everyone and everything there is fair game.”

The law, after all, gives the photographer the right to document whatever they wish in public spaces, and I therefore find it difficult to see why, for example, it should be more acceptable for private and governmental actors to document people without their knowledge through surveillance cameras — or how news reports can film individual people and crowds in the street entirely without question. In this regard, I find that street photography, in a way, democratises what may be photographed and documented. In today’s media world and extensive surveillance culture, a large portion of power lies with the commercial and the governmental, which for many years have had free rein to document people, events, and personal data. I wonder what will happen in the long run if all documentation of the city and its people comes from the perspective of privately owned companies or government authorities. In this context, I feel that street photography becomes highly un-dramatic.

The Camper

In his book How I Make Photographs (2020), Joel Meyerowitz talks about the photographer’s tendency to seek out unique places and subjects, where the obviously extraordinary is what makes us press the shutter. Something that, of course, has its place — but in one chapter of the book, Meyerowitz argues for embracing the everyday; the ordinary. He speaks of the importance of simply standing in one place. It can be a square, a café, or a street corner — somewhere where the location itself is not the obvious subject, where you simply exist without doing anything, where you have a passive role. You “camp.” Eventually, he argues, a way of seeing is created for things we had not noticed before.

“Gradually, the boredom or the blankness you might be feeling goes away, because you’re watching ordinary things unfolding their possibilities right in front of you. Then, because you’re there, something out of the ordinary will come along and suddenly you’ll see how interesting it is.”

I find it deeply fascinating how, by slowing down, taking our time, and actually waiting, we can develop a way of seeing subjects and events that we would otherwise have passed by. While it is an exciting method, I also think there is something beautiful in the approach itself. I feel that in today’s connected world, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to maintain attention, and it seems as though the concept of “boredom” is beginning to disappear altogether. We live among constant dopamine hits and continuous stimulation, where our attention has left reality and shifted to the screen. Therefore, there also lies a symbolic value in seeing by slowing down.

Pic. 13, Joel Meyerowitz. Fifth Avenue, New York. (1969)

In the image above, Meyerowitz has positioned himself at a street corner. A composition that, certainly, is visually appealing due to New York’s architecture, but it is far from an obviously striking subject. However, because Meyerowitz has allowed himself to wait, a situation arises — in this case, a confrontation between a man and a woman — which provides the photograph with an entirely new tension.

If we look at Picture 14 below, Meyerowitz has placed himself by a fountain with an accompanying flower arrangement, where we see a woman walking past with a similar bouquet of flowers in her hand. This image is fascinating for several reasons, but in connection with this discussion, it must be mentioned that the “camper” method creates a moment by waiting for chance. The fountain is lovely, certainly, but it is the fact that the woman’s own bouquet seamlessly blends with the fountain’s arrangement that gives the photograph its weight. What are the odds? It is the charged event — the moment — that constitutes the very essence of both images, something that would have disappeared had he not… waited.

Pic. 14, Joel Meyerowitz. Paris, France. (1967)

Furthermore, it is my view that “The Camper” must nonetheless be considered an approach with a more defensible ethical foundation than the other methods discussed in this text. Since the photographer stands where they stand and instead lets people and events wander into the frame, an impression is created that the photographer has already “claimed” the space. By this point, the photographer almost has greater ownership than the general public. From a social-psychological perspective, it seems that people have a broader understanding of a stationary photographer who openly shows that they are taking pictures. People apologise, bend down to stay below the frame, and wait until the photograph has been taken.

It is an extreme difference compared to the moving photographer who wanders among the crowds and encounters entirely different gazes (The Observer & The Intruder). But here, for some peculiar reason, it seems socially acceptable. This may have to do with a general perception of the photographer’s intentions — that people believe the picture is of a larger subject, an object, or a thing, rather than of an individual person. That one does not feel exposed or singled out.

One theory might also be that we all have an underlying respect for the tourist and the tourist’s right to document their experiences. In any case, the phenomenon is something I constantly encounter in my own practice, where people mistake my photographing as being directed at objects or broader environments. In fact, this makes my job easier and reduces the risk of confrontation, since people’s reactions can shift from questioning to apologetic when they, in their minds, conclude that I am photographing something other than themselves.

In reality, I pretend to hold the composition in place to mislead their thoughts. I play with the truth — which naturally has its ethical complications — but the general theory remains: there exists a completely different kind of acceptance within this method that cannot be found in the other approaches.

Focal Lengths

Another essential part of this discussion is the consideration of how the photographer positions themselves in relation to their subjects — that is, how close or far away one is from the people being photographed.

I therefore think that the focal length affects the photographer’s behaviour and attitude toward the crowd. Focal lengths of about 50mm and below produce, in my opinion, an entirely different sense of presence and honesty than longer focal lengths of 135mm and upwards. They force the photographer to relate more directly to the people around them, to exist in the present rather than observe from a distance. In a way, it feels more sincere.

In a 2019 interview with Martin Parr, Bruce Gilden explains — somewhat comically — how he also believes it is more acceptable to work close than from afar:

“I think people have this misconception that if you work close and you work with flash, it’s any more aggravating than just having your picture taken. I mean, I know for me if someone took a picture of, let’s say, my daughter and you’re from across the street, that might upset me more than someone who was in your face, because that, to me, is sneaky.”

My perception is that, in a way, it is possible to hide behind focal length. I remember from my early attempts within street photography that I often worked with focal lengths of 135mm or more. I could observe people from a greater distance and thus stayed further away from confrontation. There was a fear of potential reactions that I found uncomfortable, and for that same reason, there was a sense of security in using equipment that physically forced me to keep my distance.

What I now feel, however, is that I distance myself from the moments and people I find interesting through that kind of optics. It also contributes to a kind of passivity and cowardice that I strongly dislike. It is my view that an image can be both honest and unethical at the same time. And if it is equally unethical for someone to suddenly have their picture taken — regardless of the circumstances — then I might as well own my unethical act rather than hide behind it. That method simply feels faint-hearted and is perhaps even something that threatens the photographer’s integrity.

Handling the Camera

Furthermore, I want to emphasize something as seemingly elementary as how the photographer positions the camera close to the body and how it is maneuvered. It may sound simple, but this detail involves a number of complex decisions that also affect the relationship between the photographer and the subject.

Looking at Meyerowitz’s process, we can observe from various archival materials from the field that he both sees and creates photographs through the viewfinder, a very conventional method. Since it is generally known that the first thing the human eye focuses on when looking at other people is the eyes themselves, the presence of the camera becomes even more apparent when it is placed near the face. I mean, there is an openness on the part of the photographer when the camera in this case is used as a natural extension of human vision. Anyone can see that you are photographing, and this awareness affects the images. It is a very direct way of photographing and a method that almost certainly meets with glances due to the camera’s natural placement.

At the same time, while a certain power balance naturally arises in favor of the photographer — when a stranger suddenly encounters a camera lens — this placement can also be seen as a somewhat more natural exchange of glances, since the photographer is seeing through their natural line of sight. When the subject looks into the camera, they are thus seeing the photographer’s eyes, and vice versa. After all, it is two gazes meeting; the only difference is that the camera and its optics are positioned within the field of vision.

Someone who, however, creates a more uneven power balance is Gilden. He even extends his equipment by holding the camera in one hand and the flash in the other, creating a very unnatural encounter that extends beyond the human and the natural. The Intruder, therefore, establishes a more confrontational relationship with the subjects, with an uneven power balance.

What also creates an uneven power balance is when the camera is deliberately positioned outside the natural line of sight, something we can observe in Maier’s photographs. In many of her images, a subtle downward angle can be discerned. In many of her self-portraits through mirrors or windows, we can see that she mostly keeps a Rolleiflex camera at her waist. In my opinion, this placement contributes to a degree of anonymity. The likelihood that people notice the camera is significantly lower in this case because it is outside the eye’s instinctive field of vision. Very little body movement is required; often a small glance down into the viewfinder is enough to compose a shot.

The camera’s positioning, therefore, helps Maier come extremely close to people without their awareness. I myself have positioned the camera this way to access personal spaces and to avoid “revealing” my role as photographer/The Observer. It enables a kind of access to moments that I might not have had the courage to approach with the camera fully visible, or to moments I do not want to influence, where it is crucial that the event remains intact.

While I feel a great fascination with how well the method works for capturing intact moments, I also experience a profound sense of shame at the fact that I am peeking at people. I have a sense that there is something boundless in documenting something of which the person in question is unaware. But is it really wrong to be curious about other people? Perhaps not. Still, I struggle to escape the feeling that a camera lens positioned at the waist is somehow more perverse than my own eyes.

Final Comment

From this essay, it can be concluded that The Observer, The Intruder, and The Camper each have their advantages and disadvantages. The Observer can provide access to private moments and has a fascinating ability to encapsulate events; at the same time, the role’s invisibility presents a problem because it grants the photographer power over the editorial handling of the image. The Intruder faces a difficult task when confronted with unpredictable social situations that require quick thinking. The combination of acting impulsively, controlling technical equipment, and responding to other people according to social signals without causing conflict or producing a poor image is, after all, a skill worthy of admiration. Yet the fact remains that there is an ethical dilemma in photographing people in such an aggressive and unflattering manner, even if the law permits it.

The Camper enables an eye-opening, detail-oriented perspective on the world through waiting for chance, and is potentially the most ethically defensible of the three due to the perception that the photographer sometimes has greater ownership of the space than the passing pedestrian. At the same time, this illusion can prove problematic, as the photographer may thus manipulate the truth about the subject. Furthermore, it can be argued that focal length creates different distances to the subjects being photographed, with longer focal lengths potentially being perceived as more sneaky and dishonest. Finally, the physical placement of the camera close to the body creates varying degrees of anonymity, which can serve as a tool depending on which role the photographer assumes.

Ultimately, the discussion should perhaps not be about what is right or wrong, good or bad. Rather, it should focus on how the photographer can reason in relation to their decision-making. To understand in the moment how a subtle adjustment in camera placement provokes different types of reactions in the subjects, or how positioning and waiting for chance can either drain or charge a photograph completely. To understand that different methods carry ethical consequences and to be able to argue for the choices one makes. We live in a society in constant change, where questions of surveillance and public space are increasingly debated. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that the street photographer preserves and values reflective action, so that the fear of doing wrong does not override curiosity about the world. It is thus my final conclusion that if that ability dies, street photography itself dies as well.

References

A. D. Coleman, Private Lives, Public Places: Street Photography Ethics, Journal of Mass Media Ethics, vol. 2, 1987.

B. Koszowski, Street Photography: Ethics, Consent, Privacy, and New Technologies, Lens Odyssey, 2023, [online]. Available at: www.bmkoszowski.com (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

Britannica, N. Blumberg, Street Photography, Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/street-photography (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

D. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, Basic Books, 1983.

G. Williams, “Greg Williams on Instagram: ‘In this snippet from my @Skillsfaster Candid Photography Course…’”, Instagram, 2020. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CrJNeoGuwXo/ (Accessed: 29 October 2024).

J. Meyerowitz, How I Make Photographs, Laurence King, 2020.

Maloof Collection Ltd., History, Vivian Maier Photographer. Available at: https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/history/ (Accessed: 29 October 2024).

M. Parr Foundation, How Does Bruce Gilden Photograph People Close-Up?, YouTube, 25 April 2019. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pnVLkTohlo (Accessed: 29 October 2024).

MIT Press, Reflective Practice: Theory and Art in Action, MIT Press, 2024. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/reflective-practice (Accessed: 15 November 2024).